Improving Ankle Dorsiflexion: How to Do It?

VOETBAL MEDISCH SYMPOSIUM 2020

DE BEHANDELING VAN VOETBALBLESSURES

PRAKTISCHE WETENSCHAP

OP DE KNVB CAMPUS IN ZEIST VINDT KOMEND JAAR OPNIEUW HET VOETBALMEDISCH SYMPOSIUM PLAATS.

HET SYMPOSIUM IS DÉ PLEK OM COLLEGA’S BINNEN HET VOETBALMEDISCHE DOMEIN TE ONTMOETEN OF KENNIS OP TE DOEN VAN GERENOMMEERDE EXPERTS. EN DIE NIEUWSTE INNOVATIES TE ZIEN OP HET GEBIED VAN VOETBALMEDISCHE EN FYSIEKE PRESTATIES.

NA VORIG JAAR DE DIAGNOSTIEK VAN VOETBALBLESSURES BELICHT TE HEBBEN, ROLT DE BAL DIT JAAR VERDER NAAR DE BEHANDELING VAN VOETBALBLESSURES. HET INHOUDELIJKE PROGRAMMA BIEDT OPNIEUW SPREKERS DIE ZICH ONDERSCHEIDEN IN ZOWEL DE DAGELIJKSE ZORG VOOR DE VOETBALLERS ALS OP WETENSCHAPPELIJK GEBIED.

VOETBAL MEDISCHE WORKSHOP 2020

(VELD)REVALIDATIE NA EEN VOETBALBLESSURE

OP 4 MAART ZAL ER WEDEROM EEN WORKSHOP PLAATS VINDEN BIJ HET KNVB VOETBAL MEDISCH CENTRUM.

OOK DIT JAAR BELOOFD HET EEN OCHTENDVULLEND PROGRAMMA TE ZIJN WAAR VOORNAMELIJK (SPORT)FYSIOTHERAPEUTEN HUN KENNIS MEE KUNNEN UITBREIDEN.

TIJDENS DE WORKSHOP ZAL MATT TABERNER ZIJN KENNIS EN EXPERTICE MET DE DEELNEMERS GAAN DELEN. MATT TABERNER IS EEN ERVAREN CLINICUS DIE AL JAREN EINDVERANTWOORDELIJK IS VOOR DE REVALIDATIE VAN TOPVOETBALLERS IN DE PREMIER LEAGUE. ZIJN FOCUS LIGT VOORNAMELIJK OP FYSIEKE ONTWIKKELING EN PRESTATIES. TEVENS IS HIJ DE ONTWIKKELAAR VAN HET ‘CONTROL-CHAOS CONTINUUM’.

DIT FRAMEWORK, WELKE VIJF FASES BESCHRIJFT HOE DE VELDREVALIDATIE NA EEN VOETBALBLESSURE OPGEBOUWD KAN WORDEN, STAAT CENTRAAL BINNEN DE WORKSHOP. DE THEORETISCHE ACHTERGROND,

DE TOEPASSING EN HET PRAKTISCHE ASPECT ZULLEN ALLEN AAN BOD KOMEN TIJDENS DE WORKSHOP.

reviews

Nick van der Horst

Meet the soccerdoc

Nick van der Horst behaalde zijn diploma fysiotherapie in 2007 aan de Hogeschool Utrecht. Hij werkte 10 jaar lang als sportfysiotherapeut/echografist/docent bij het Academie Instituut te Utrecht. Daarna heeft hij de overstap gemaakt naar waar zijn hart ligt, het professionele voetbal. Hij heeft twee jaar als sportfysiotherapeut en hoofd van de medische staf bij Go Ahead Eagles in Deventer gewerkt. Momenteel is is Nick werkzaam bij de KNVB. Zijn onderzoeks-activiteiten zijn gefocust op de voetbal-medische zorg. In 2017 behaalde hij zijn doctoraal na het verdedigen van zijn proefschrift ‘Prevention of hamstring injuries in male soccer’.

Blogger: Raúl Gómez

There are hundreds of variations of ankle mobility exercises on the internet, but while mobility training is an essential part of any training program, improving the range of motion (ROM) of a chronically restricted joint can be much more complex than doing a couple of stretches after training.

In the previous two articles, we discussed how limited ankle mobility can affect lower limb movement mechanics and explored various ankle dorsiflexion assessment methods. Now, it is time to design a training program for soccer players with ankle mobility restrictions.

In the book “Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance. The Janda Approach”, we find a very interesting classification of the musculature that tends to overactivation and the one that tends to weakness or inhibition. In the case of the ankle, the authors of this book state that the triceps surae muscles, especially the soleus, are prone to overactivation and stiffness, while other anterior lower leg muscles, such as the tibialis anterior, are prone to muscle weakness and inhibition. Authors such as Utku et al. (2018) have shown in their research the difference in the activation and inhibition patterns of the muscles of the triceps surae and the tibialis anterior. Their research showed stronger inhibition of the tibialis anterior compared to the triceps surae, which could be associated with specific neural control strategies of posture (Utku et al., 2018).

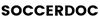

To address the muscular imbalance in the ankle joint, it is important to reduce the excessive tension and shortening of the posterior muscles while also activating and strengthening the anterior muscles. In a study by Lee et al. (2021), the effects of stretching the triceps surae alone were compared with the effects of combining the triceps surae stretching with tibialis anterior strengthening exercises (Image 1). The results showed that the group that performed the combination of triceps surae stretching and tibialis anterior strengthening increased ankle dorsiflexion ROM more than the group that performed stretching alone. After the exercises, the activity of the tibialis anterior muscle increased. The authors suggest that this increase could lead to reciprocal inhibition of the triceps surae musculature, thus increasing the ROM of the ankle. It is important to note that this study only looked at the immediate effects of the intervention, and there is very little research on the long-term effects of this type of intervention. Therefore, we do not know the chronic effects of applying this type of exercise.

Image 1. Tibialis anterior resistance exercise

Static stretching has been proven to effectively improve flexibility and performance and reduce delayed-onset muscle soreness in the long term. However, it may have negative acute effects on muscle strength, potentially impairing sports performance (Grieve et al., 2022). On the other hand, alternative techniques like myofascial release have been shown to enhance the ROM without negatively affecting performance.

The use of the Foam Roller (FR) (Image 2) has gained much popularity in recent years, although many people are still unaware of its effects and how to use it properly. The review by Grieve et al. (2022) showed that the use of FR is effective in improving short-term ankle dorsiflexion ROM without detrimental effects on performance, making it a viable alternative to static stretching during warm-up. This improvement may be due to increased muscle temperature and pressure after using the FR. These changes would cause alterations in the density and fluidity of the muscle tissue (Aune et al., 2019). Other theories have also been suggested, such as the activation of the parasympathetic system after pressure is applied to the muscle. This activation would influence neural activity and reduce muscle tone (Aune et al., 2019).

Image 2. Self-myofascial release with Foam Roller

More research is needed regarding the long-term effects of FR since the investigations’ results are very different due to the significant difference between protocols. In the review previously mentioned, most studies use the FR for 1.5 to 3 minutes, applying as much pressure as possible. The tempo of FR varies significantly across studies, making it very difficult to draw conclusions about it.

Another alternative to static stretching is dynamic stretching, which would be done in the same positions as static stretching but moving through the full ROM at a set pace.

The inclusion of this type of stretching of the lower limb muscles, including exercises for gastrocnemius and soleus (Image 3), has shown not only short-term improvements in ankle mobility but also improvements in performance compared to a protocol that did not include dynamic soleus stretches (Huang et al., 2022).

Image 3. Gastrocnemius (left) and soleus stretching (right)

The results of these investigations suggest that combining FR with dynamic stretching may be a viable way to acutely improve ankle mobility and sports performance (Little & Williams, 2006).

This approach may be used during warm-ups prior to high-intensity sessions or competitions, although further research is necessary to determine the best way to apply both interventions.

Ankle dorsiflexion can also be limited by the restriction of posterior talus gliding, which is an essential movement for proper ankle joint motion (Jeon et al., 2015). To address this limitation in intra-articular mobility, mobilization techniques involving manual traction or straps have been suggested to assist with the posterior gliding of the talus during ankle dorsiflexion.

Jeon et al. (2015) compared the effect on ankle mobility of performing static triceps surae stretching alone with performing the same stretches using a strap that assisted posterior talus glide. In this technique, the strap was placed around the anterior aspect of the talus of the front foot, which was placed on a 10º inclined board. The other part of the strap was placed around the rear foot, which was on the ground, applying force on the front foot in a posteroinferior direction (Image 4).

Image 4. Ankle self-stretching using a strap (Jeon et al., 2015)

From this position, the patient was asked to move the knee forward without pain or discomfort until stretching of the soleus of the front leg was felt.

This final position was held for 20 seconds. 15 repetitions were performed, with a 10-second rest between stretches. This intervention was performed 5 times a week for 3 weeks in both groups. The group that performed stretching with the assistance of a strap showed better results compared to those who only did stretching in terms of active and passive ankle dorsiflexion and flexion angle during a closed kinetic chain test.

Similarly, Kang et al. (2015) examined the effects of combining static stretching with talocrural mobilization. In this case, the therapist assisted the posterior gliding of the talus with his hand (see Image 5). The stretches were performed in 10 repetitions of 30 seconds with 30 seconds of rest between repetitions.

This study also found superior effects of this type of mobilization compared to static stretching alone regarding increased ankle dorsiflexion, time to heel-off during gait, and posterior gliding of the talus.

Image 5. Manual talocrural mobilization (Kang et al., 2015)

Although eccentric exercise has been shown to increase muscle fascicle length effectively (Harris-Love et al., 2021), there is controversy surrounding its impact on improving ankle mobility. While authors such as Aune et al. (2019) have shown improvements following a training plan that included eccentric exercises, others such as Lagas et al. (2021) did not find any benefit; in fact, they observed a decrease in the flexibility of the triceps surae musculature.

This may be due to the difference between protocols. Lagas et al. (2021) performed the exercises 3 times per week following a progression that began with a very low training volume, 2 sets of 4 repetitions. The volume increased by about 20% each week until finishing the last week doing 3 sets of 15 repetitions. In the other study, Aune et al. (2019) performed the exercises daily for 4 weeks, starting directly with 3 sets of 15 and maintaining the same training volume throughout the intervention. Although eccentric training has been shown to be effective in improving muscle flexibility, more research is needed to determine the optimal training dose to improve ankle dorsiflexion ROM.

Certain medical conditions can limit joint ROM and need special clinical evaluation, but these cases are beyond the scope of this article.

In summary, a training plan aimed at improving ankle dorsiflexion ROM should include the following:

- Myofascial release of the triceps surae

- Talocrural mobilization with assistance to the posterior gliding of the talus

- Stretching of the triceps surae (Dynamic stretching is recommended if performed before competition or training with high-intensity actions)

- Specific strengthening of the dorsiflexor muscles

- Eccentric exercises

Although isolated exercises can be very useful in improving certain risk factors for soccer injuries, we cannot forget that human movement is much more complex than the movement of a single joint. After correcting movement and strength deficits, sport-specific activities should be trained, including multi-articular exercises, plyometrics, and high-intensity actions such as sprinting, jumping, and changes of direction.

Injury prevention is a very complex process that requires daily effort. Achieving adequate mobility of all joints is critical to improving performance and minimizing the risk of severe injuries. As shown, the ankle joint plays a vital role in this process.

References

Aune, A. y otros, 2019. Acute and chronic effects of foam rolling vs eccentric exercise on ROM and force output of the plantar flexors. Journal of Sports Sciences, pp. 138-145.

Grieve, R. y otros, (2022). The effects of foam rolling on ankle dorsiflexion range of motion in healthy adults: A systematic literature review. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, pp. 53–59.

Harris-Love, M., Gollie, J. & Keogh, J. (2021). Eccentric Exercise: Adaptations and Applications for Health and Performance. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology, 6(96).

Huang, S. y otros, 2022. Acute Effects of Soleus Stretching on Ankle Flexibility, Dynamic Balance and Speed Performances in Soccer Players. Biology, 11(374).

Jeon, I.-C.y otros, 2015. Ankle-Dorsiflexion Range of Motion After Ankle Self-Stretching Using a Strap. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(12), p. 1226–1232.

Kang, M.-H.y otros, 2015. Immediate combined effect of gastrocnemius stretching and sustained talocrural joint mobilisation in individuals with limited ankle dorsiflexion: A randomised controlled trial. Manual therapy, Volumen 20, pp. 827-834.

Lagas, I. F. y otros, 2021. Effects of eccentric exercises on improving ankle dorsiflexion in soccer players. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 22(485).

Lee, J., Cynn, H., Shin, A. & Kim, B. (2021). Combined Effects of Gastrocnemius Stretch and Tibialis Anterior Resistance Exercise in Subjects with Limited Ankle Dorsiflexion. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science, 10(1), 10–15.

Little, T. & Williams, A., 2006. Effects of differential stretching protocols during warm-ups on high-speed motor capacities in professional soccer players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(1), pp. 203-207.

Page, P., Frank, C. & Lardner, R., (2012). Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance: The Janda Approach. Windsor, Ontario, Canada: Human Kinetics.

Utku, Y., Negro, F., Diedrichs, R. & Farina, D., 2018. Reciprocal inhibition between motor neurons of the tibialis anterior and triceps surae in humans. Journal of Neurophysiology, pp. 1699-1706.